Just a few days ago, I saw a post from the Stranraer Museum regarding the fragments of a lunulu found near Cruggleton, Wigtownshire, Scotland. If you aren’t familiar with what a lunula (plural = lunulae) is… I recommend a quick look at Wikipedia’s entry for “Gold Lunula”. Here’s what Stranraer Museum had to say about the fragments of the one on display with them:

A 4000 year old mystery… These fragments of beaten gold were made around 2200 BC and were found near Cruggleton, Wigtownshire. They had been deliberately cut and then rolled into a small package before being deposited in a hole in a field. Originally, they would have formed a large collar or neck ornament (sometimes called a lunala, referring to its crescent moon shape). The stunning, glittering gold was intensified by precise decorative lines which can still be seen around the edge of the piece. We know very little about the use and meaning of this object but we can safely assume that this collar would have been worn by a high status individual/s, possibly for religious purposes.

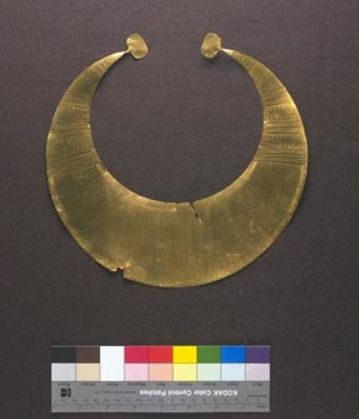

Lunulae are rare but have been found all over the UK, including six complete examples in Scotland. The Cruggleton fragments form about one third of a collar – compare these to a complete lunula from Auchentaggart, Dumfriesshire (below). (Auchentaggart – translates as ‘Field of the Priest’).

The fragments were found by a metal detectorist. Archaeological examination of the find spot failed to recover any other fragments or related objects – this is important, as this lunula could well be two ‘hoarded’ pieces of gold, buried perhaps for a rainy day. This is likely, as the gold was rolled up – i.e., the damage to the piece was not caused by ploughing or digging.

Most lunulae were found singly or sometimes (as at Harlyn, Cornwall and Coulter, Lanarkshire) in pairs, deposited on their own or possibly in a box or pouch.All the complete Scottish lunulae were found close to rivers, whilst the Cruggleton fragments echo the find spot of the Harlyn Bay Lunulae, close to the sea shore. What did these depositions mean? Is the burial near water significant? We may never know… Let us know your theories and thoughts!

Of course, given my Y DNA work, connecting the Damnonii of SW Scotland with the Dumnonii of SW England, it shouldn’t be a surprise that the post immediately caught my eye… especially when they mentioned this piece along with a reference to another, previously found in Harlyn, Cornwall. As I’ve mentioned before, I’m pretty new to the study of archaeological findings in the UK, but the post made me wonder about a few things. Most importantly, given the age of this linula and others found in SW Scotland (as well as one in nearby Cumbria), might this be an indicator as to when the Celtic Britons arrived there?

Here are links to details about the different pieces of interest (Most of these are National Museums Scotland links):

Lunula from Cruggleton, Wigtownshire, ca. 2200 BC

Linula from Southside, near Coulter, Lanarkshire, ca. 2200 – 1700 BC

Linula from Auchentaggart, Dumfriesshire, ca. 2300 – 2000 BC

Linula from either Lanarkshire or Ayrshire, ca. 2300 – 2000 BC

Linula from Brampton, Cumbria, ca. 2400 – 2000 BC

Linula from Harlyn, Cornwall, ca. 2200 – 1950 BC

Sure, many more have been found over the years (significantly more in Ireland… and, remember, yes, Celtic Britons were in Ireland), including some in Brittany, France (yes, Celtic Briton) and Portugal (possibly Celtic Briton)… and in Germany. My point is, while we know there are Bronze and Iron Age archaeological finds in Ayrshire, Lanarkshire, etc., it seems difficult to make a confident claim that those items connect to the same people later known as the Damnonii. Even so, the connection seems possible (probable?) they do tie together. Ultimately, it’s prehistory… a story with no paper trail. We have nothing to rely upon except archaeological finds, and what they may tell us. As for me, I feel the link is likely, and it’s inspiration to look into those archaeological ties even more.